- Home

- Richard Matheson

The Incredible Shrinking Man Page 16

The Incredible Shrinking Man Read online

Page 16

Chapter Sixteen

In the distance he could hear the thumping of the water pump. They forgot to turn it off. The thought trickled like cold honey across the fissures of his brain. He stared with vacant eyes, his face a blank. The pump clicked off, and silence draped down across the cellar. They're gone, he thought. The house is empty. I'm alone.

His tongue stirred sluggishly. Alone. His lips moved. The word began and ended in his throat. He twisted slightly and felt a stirring of pain in the back of his skull. Alone. His right fist twitched and thumped once at the cement. Alone. After everything. After all his efforts, he was alone in the cellar. He pushed up finally, then sank down instantly as pain seemed to tear open the back of his head. Lying there, he reached up gingerly and touched a finger to the spot. He traced the edges of the brittle lacework of dried blood; his fingertip ascended and descended the parabola of the lump. He prodded it once. He groaned and dropped his arm. He lay there on his stomach, feeling the cold, rough cement against his forehead.

Alone.

Finally he rolled over and sat up. Pain rolled sluggishly around the inside of his head. It did not stop quickly. He had to press the palms of his hands against his temples to cushion its stabbing rebound. After a long while it stopped and dragged down at the base of his skull, spikes sunk in his flesh. He wondered if his skull were fractured, then decided that, if it were, he would be in no condition to wonder about it. He opened his eyes and looked around the cellar with pain slitted eyes. Everything was still the same. His dismal gaze moved over the familiar landmarks. And I thought I was going to get out, he thought bitterly. He looked up over his shoulder with a wince. The door was closed again, of course. And locked too, probably. He was still trapped.

His chest shuddered with a long exhalation. He licked his dry lips. And he was thirsty again too, and hungry. It was all senseless.

Even the slight amount of tensing in his jaws sent pain gnawing through his head. He opened his mouth and sat limply until the aching had diminished.

When he stood, it came back again. He pressed one palm against the face of the next step and leaned against it, the cellar wavering before him as though he saw it through a lens of water. It took a while for objects to appear clearly.

He shifted on his feet and hissed, discovering that his knee was swollen again. He glanced down at its puffiness, remembering that it was the leg that had been injured in his original fall into the cellar. Odd that he'd never made the connection, but that was undoubtedly why that leg always weakened first. He remembered lying on the sand, the leg twisted under him, while outside Lou was calling him. It was night and the cellar had been dark and cold. Wind had blown snow confetti through the broken pane. It had drifted down across his face, feeling like the timid, withdrawing touches of ghostly children. And, though he answered her and answered her, she never heard him. Not even when she came down into the cellar and, unable to move, he had lain there, crying out her name.

He walked slowly to the edge of the step and looked down the hundred foot drop to the floor. A terrible distance. Should he labour down the mortar-crack chimney or abruptly, he jumped. He landed on his feet. His knee seemed to explode and a knife-edged club smashed across his brain as he fell forward to his hands. But that was all. Shaken, he sat on the floor, smiling grimly despite the pain. It was a good thing he'd discovered that he could fall so far without being hurt. If he hadn't discovered it, he would have had to climb down the chimney and wasted time. The smile faded. He stared morosely at the floor. Time was no longer something to be wasted, because it was no longer something to be saved. It was no longer a commodity to be spent or hoarded. It had lost all value. He got up and started walking, feet padding softly over the cold cement. Should have got the sponge shoes, he thought. Then he shrugged carelessly. What did it matter, anyway?

He got himself a drink from the hose, then returned to the sponge. He didn't feel hungry, after all. He climbed to the top of the sponge and lay back with a thin sigh.

He lay there inertly, staring up at the window over the fuel tank. There was no sunlight visible. It must be late afternoon. Soon darkness would fall. Soon the last night would begin. He looked at the twisted latticework of a spider web that blocked off one corner of the window. Many things hung from its adhesive weave, dust, bugs, bit of dead leaf, even a stubby pencil he had thrown up there once. In all his time in the cellar he'd never seen the spider that made that web. He didn't see it now.

Silence hung over the cellar. They must have turned off the oil heater before they left. There was that faint crackling, creaking sound of warping boards, but that couldn't even scratch the surface of the silence. He could hear his own breath, uneven and slow.

Through that window, he thought, I watched that girl. Catherine; was that her name? He couldn't even recall what she'd looked like.

He'd also tried to get up to that window after he'd fallen into the cellar. It had been the only one available. The window with the broken pane was too far above the sand, only a vertical wall beneath it. The window over the log pile was even less accessible. The only one that had presented the slightest possibility had been the one over the fuel tank.

But, at seven inches, he hadn't been able to climb the boxes and suitcases. And, by the time he'd found the means, he was too small. He'd gone up there once, but, without a stone, he'd been unable to break the pane and had had to go down again.

He rolled over on his side and turned away from the window. It was unbearable to see sky and trees and know he'd never be out there again. He breathed heavily, staring at the cliff wall. And here I am, he thought, back to morbid introspection again; all action undone. This could have ended long ago. But he had had to fight it. Climb threads, kill spiders, look for food. He clamped his mouth shut and stared at the long net pole leaning against the cliff wall, the long pole leaning against the wall. His gaze moved along the pole leaning against the wall, the long pole leaning against the wall. He jerked up suddenly.

With a breathless grunt, he scrambled to the edge of the sponge and jumped down, ignoring the pain in his knee and head. He started racing for the cliff wall, stopped. What about water and food? Never mind, he wouldn't need it; it wasn't going to take that long. He ran toward the pole again. Before he reached the net, he ran into the hose and got a drink. Then, running out again, he began to shinny up the metal rim of the net past the body-thick cords. He climbed until he'd reached the pole, then pulled himself up onto its wide, curving surface.

It was better than he'd imagined. The pole was so wide and it was leaning against the wall at such a low angle that he wouldn't have to clamber up, hands down, for support. He could almost run erect up the long, gradual slope. With an excited cry he started up the road to the cliff. Was it possible, he wondered as he ran, that things had worked out in a definite manner? Was it possible that there was purpose to his survival? It was hard to believe, and yet, in a greater measure, hard to disbelieve. All the coincidences that had contributed to his survival seemed to go beyond the limits of probability.

This, for instance; this pole thrown here in just this way by his own brother. Was that only chance?

And the spider's death yesterday providing the final key to his escape. Was that only chance? Most importantly, the two occurrences combining in just this way to make possible his escape. Could it be only coincidence?

He could hardly believe it. Yet how could he doubt the process going on in his body, which told him clearly that he had today and nothing more? Unless the very precision with which he shrank indicated something. But indicated what, beyond hopelessness?

Still he did not lose the shapeless feeling of excitement as he hurried up the broad pole. It was still rising when he passed the first lawn chair; rising when he passed the second; rising when he stopped and sat looking down at the vast gray plain of the floor; rising when, an hour later, he reached the top of the cliff and fell down, exhausted, on the sand. And it was still rising as he lay there, heart poun

ding, fingers clutching at the sand. Get up, he kept telling himself. Let's go. It will be dark soon. Let's get out before it's dark.

He got up and started running across the shadowy desert. After a while he passed the silent bulk of the spider. He didn't stop to look at it; it was not important now. It was only a step already taken, which provided the ground for the next step. He stopped only once, to pull loose a chunk of bread and shove it under his coat of sponge. Then he ran on again.

When he reached the spider's web, he rested a while, then began to climb. The cable was sticky. He had to pull his hands and feet loose from it before he could climb up to the next one. The web trembled and swayed beneath his weight as he climbed past the dead beetle, not looking, breathing through his mouth.

And still excitement rose. Suddenly everything seemed meaningful, as if things had to happen in just this way. He knew it might be the rationalizing of desire, but he couldn't help thinking it anyway. He reached the top of the web and quickly climbed onto the wooden shelf that ran around the wall. He could run now, and he did, his feet pounding down with a strong rhythm. He ignored the throbbing of his knee; it didn't matter.

He ran as fast as he could. Three blocks this way along the shadow-dark path, around the corner at top speed, then a mile straight ahead. He skittered like a tiny bug along the beam, running until he could hardly breathe.

He ran into blinding light.

He stopped, chest lurching, hot breath spilling from his lips. He stood there, eyes closed, and felt the wind blowing across his face. He closed his eyes and sniffed at its sweet, clear coolness. Outside, he thought. The word ballooned in his brain until it crowded out everything else and was the only word left. Outside. Outside. Outside.

Quietly then, slowly, with a dignity befitting the moment, he pulled himself up the few inches to the open square of window, clambered over the wooden rim, and jumped down. He stepped across the cement walk on trembling legs and stopped.

He stood at the edge of the world, looking.

He lay on a soft mattress of sere, crinkly leaves, other leaves pulled over him, the vast house behind him, blocking off the night wind. He was warm and fed. He'd found a dish of water underneath the porch, and had drunk from it. Now he lay there quietly on his back, looking at the stars. How beautiful they were; like blue-white diamonds cast across a sky of inky satin. No moonlight illuminated the sky. There was only total darkness, broken by the flaring pin points of the stars. And the nicest thing about them was that they were still the same. He saw them as any man saw them, and that brought a deep contentment to him. Small he might be, but the earth itself was small compared to this.

Odd that after all the moments of abject terror he had suffered contemplating the end of his existence, this night, which was the very night it would end, he felt no terror at all. Hours away lay the end of his days. He knew, and still he was glad he was alive.

That was the wonderful part of this moment. That was the thick blanket of contentment that warmed his toes. To know the end was close and not to mind. This, he knew, was courage, the truest, ultimate courage, because there was no one here to sympathize or praise him for it. What he felt was felt without the hope of commendation.

Before, it had been different. He knew that now. Before he had kept on living because he had kept on hoping. That was what kept most men living.

But now, in the final hours, even hope had vanished. Yet he could smile. At a point without hope he had found contentment. He knew he had tried and there was nothing to be sorry for. And this was complete victory, because it was a victory over himself.

"I've fought a good fight," he said. It sounded funny to say it. He felt almost embarrassed. Then he shook away embarrassment. It was what was left to him. Why shouldn't he proclaim the bitter sweetness of his pride?

He bellowed at the universe. "I've fought a good fight!" And under his breath he added, "God damn it to hell. "

It made him laugh. His laughter was the faintest icy sprinkling of sound against the vast, dark earth. It felt good to laugh, and good to sleep, under the stars.

Earthbound

Earthbound Hunted Past Reason

Hunted Past Reason Duel: Terror Stories

Duel: Terror Stories 7 Steps to Midnight

7 Steps to Midnight Somewhere in Time

Somewhere in Time Ride the Nightmare

Ride the Nightmare Hell House

Hell House Hunger and Thirst

Hunger and Thirst Lyrics

Lyrics Other Kingdoms

Other Kingdoms Now You See It . . .

Now You See It . . . I Am Legend

I Am Legend The Box: Uncanny Stories

The Box: Uncanny Stories Camp Pleasant

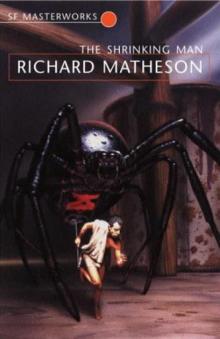

Camp Pleasant The Incredible Shrinking Man

The Incredible Shrinking Man What Dreams May Come

What Dreams May Come The Gun Fight

The Gun Fight Someone Is Bleeding

Someone Is Bleeding Mediums Rare

Mediums Rare A Stir of Echoes

A Stir of Echoes Backteria and Other Improbable Tales

Backteria and Other Improbable Tales Offbeat: Uncollected Stories

Offbeat: Uncollected Stories I Am Legend and Other Stories

I Am Legend and Other Stories The Best of Richard Matheson

The Best of Richard Matheson Shock II

Shock II Steel: And Other Stories

Steel: And Other Stories Richard Matheson Suspense Novels

Richard Matheson Suspense Novels The Link

The Link Nightmare At 20,000 Feet

Nightmare At 20,000 Feet Shadow on the Sun

Shadow on the Sun![Steel and other stories [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/21/steel_and_other_stories_ssc_preview.jpg) Steel and other stories [SSC]

Steel and other stories [SSC] Created By

Created By Offbeat

Offbeat Duel

Duel The Shrinking Man

The Shrinking Man Steel

Steel Now You See It

Now You See It